News & Resources

What Being the First in My Family to Go to College Taught Me About Opportunity

When my dad drove me from Chicago to Iowa State University, a six-hour ride in his 1965 dark blue Plymouth Belvedere wagon, we didn’t speak a word. He was anxious and angry that I had turned down an offer from the Air Force Academy. They had promised a full scholarship, room and board, summer employment and a job after I finished. “That sounds like a good deal,” he told me.

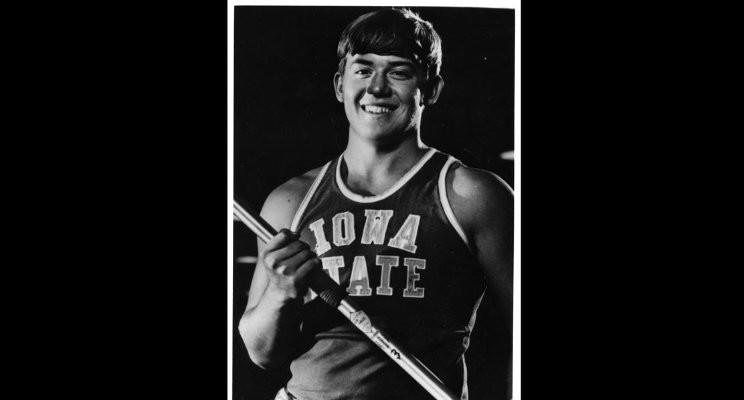

But I had something else in mind. Cobbling together an ROTC scholarship, a partial athletic scholarship and another independent scholarship, I would have enough to cover my education and expenses for four years. I could throw myself into learning, when I wasn’t busy throwing a javelin.

I was hungry and ambitious, even if I didn’t know much about this new world. “Who’s the idiot who came up with that idea?” I asked when told I couldn’t take five majors. My younger self was kind of argumentative.

I had big plans, especially because I was the first kid in my family to go to college. My dad’s family first came to Maryland in the 1640s as indentured servants, and what followed was 14 generations of farmers, builders, soldiers, sailors—largely self-taught people who served their country and worked hard.

My father continued that tradition. He was an enlisted sailor, a high school graduate, who moved my two brothers, two sisters and me 21 times before I got to college. That included stints in Maryland, Kentucky, Florida, Illinois, California and back again. I attended four different high schools, several of them more than once.

Dad did have a few words before going. “Maybe we’ll see you at Christmas,” he said, then pulled away in his Plymouth, leaving me curbside with my Boy Scout trunk containing all my worldly possessions.

*

When I was 13 and living in Lexington Park, Maryland, my fellow Eagle Scout Randy Rupp and I collected a year’s supply of food as well as holiday gifts and toys for a needy family. On Christmas Eve, 1968, we packed full two U-Haul trucks, and my dad drove one dressed as Santa. The ride didn’t take all that long, but it felt like we traveled to a different world. The family lived in a shack with a tarpaper roof and a dirt floor.

We were not exactly living like kings: My four younger siblings, dad and I lived in government housing for enlisted Navy personnel. When I was nine, not long after my mom passed away, I shared a bunk bed with one of my brothers in a makeshift room, rigged up with blankets hanging from a carport outside our house in Imperial Beach, California. I slept on the top bunk so neighborhood dogs couldn’t lick me awake.

Later that night, after visiting the tarpaper shack, I watched astronauts from Apollo 8, who circled the moon ten times. I watched on a color TV, a brand-new Magnavox set that my dad went into hock to get.

I remember that moment like it happened a minute ago. I was literally tingling and having this thought: Who were these people living in a shack, who were we, and who were these people up at the moon?

It didn’t seem fair that they had a dirt floor and we had a color television. And I was gripped by the idea that these other people took off in a rocket and flew to the moon. They were proving that you can do anything if you can get your mind ready.

I carried this feeling—this dual notion—of unfairness and the sense that anything was possible with education straight to Ames, Iowa. This fueled me, even if my dad was angry, wondering and worrying what would become of me.

*

When we arrived on campus, I was surprised to see that it was pretty empty. It turns out we were four days early. (It was the only day my dad had free to take me.) With less than ten dollars in my pocket, I wasn’t sure how I was going to get by until the dorms and the dining hall opened. But within an hour, another kid and I were offered a job assembling cots, paid with meals and a place to sleep.

Before long, my world opened up like never before. Finally, I had four straight years in one place. Growing up, one constant was the local public library or the library on base. Now not only did I have access to a great college library, but my ROTC scholarship allowed me to buy anything in the bookstore—any book, not just those on a professor’s syllabus—that I thought I needed to be successful. I couldn’t believe my good luck; I was in heaven.

Except for teachers, there wasn’t anyone I knew who had been to college. But after a sophomore high school project simulating the Apollo 13 mission, I began thinking more about how can we predict the future, design the future, and control it. I had this self-derived idea that college was the way to get the tools necessary to design things that don’t exist—not just objects, but also structures, systems, organizations.

My original plan was to study engineering, linguistics, political science, history and anthropology. There might even have been a few others. College to me was going to be a feast—and I just didn’t understand why it made sense to only major in one thing. When told that wasn’t possible, I pulled back and double-majored in political science and environmental science, taking as many of the other courses and eventually independent studies as the hours in the day allowed.

*

While I was drawn to many fields, I wanted to do more than graze. That led me to Don Hadwiger, a professor who taught science policy and food and agriculture policy. He talked about making change to make things better: For example, how do you feed more people? Science was not just about learning for the sake of knowledge, it was about solving problems.

When I was 19, a junior, some university administrators hired me to go to the Iowa state legislature to talk about a technical project involving mining coal and then restoring the farm land for greater agricultural productivity. “We have no idea how you understand this project, but you explain it better than we do,” they told me. Later they sent me off to Washington, DC, to do the same.

So here I was in college, learning about politics and engineering and science—and how science gets translated and interpreted. The school also let me design and build my own grant-funded engineering project: a system that could minimize the dust from mined coal and limit environmental effects. All of this led to working at the Ames National Laboratory right after graduation to come up with ideas and design energy-related projects.

College created this incredible environment for me to learn in the widest possible way. It allowed me to give concrete shape to my high-school-age notion that a place of learning can fuel the designer of the future; enable multiple ways of thinking, multiple pathways and subjects; and then apply that learning to drive change and make something new.

It made me think: Wouldn’t it be great if universities worked that way more broadly, engaging across disciplines to solve problems and creating opportunity for the widest possible cross-section of students to take part? This has inspired my work at ASU in designing a New American University.

My dad and I were probably equally stubborn. I can remember sleeping in the doghouse in the backyard, during a sleet storm, rather than argue with him. But he didn’t stay angry and he didn’t carry a grudge. After that first drive to college, our relationship was positive. I know he was proud of me. And I know he saw, in his way, the value of what I am trying to achieve.